In recent years an increasing number of musical scholars

have come to the conclusion that musical analysis has no

solid theoretical foundation, that the reality of the units

and relationships in terms of which analyses are formulated

has been subject to at best scanty experimental

verification, and that in many cases it is not even clear

what sort of reality these units and relationships are

supposed to have. Is a cadence an acoustic phenomenon? a

perceptual phenomenon? is it merely a convenient fiction

that one employs in specifying what the well-

Those scholars who have shared this concern about the theoretical foundations of music have sought inspiration from work in other fields to which musical analogues can be found and which thus suggest experiments that can cast light on the status of purported musical entities. A number of musical scholars have recently carried out investigations suggested by work in linguistics. Since the results of these experiments have mostly been published in relatively obscure journals such as Zentralblatt für musikalische Grundlagenforschung, Le contrebasson et la vie humaine, and Finger, which are not widely read by linguists, it may be useful to the linguistic profession if I provide here a summary of some of the more interesting studies in which linguistic research has influenced work in the foundations of music.

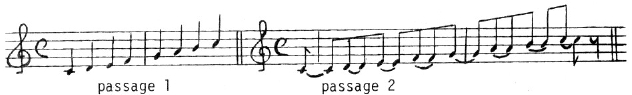

In a recent paper entitled ‘The neurological reality of the

bar line’, Walter Heppleworth reports on an

electromyographic study in which micro-

Figure 1

With ten of the eleven subjects, Heppleworth found a

consistent difference between the tracings of neurological

activity for the two passages: the syncopated passage showed

greater neurological activity, consisting, roughly speaking,

of the pattern of activity found in the unsyncopated passage

summed with a weakened repetition of certain components of

that activity following at an interval of one eighth-

I turn now to research on psycho-

Quattrostagioni’s research group has recently undertaken

studies of cerebral dominance phenomena in music. In a

draft recently circulated in mimeograph form of a paper

entitled ‘In one hemisphere and out the other’,

Quattrostagioni reports preliminary results of an ongoing

experiment in which music students, again from the

University of Reggio di Calabria, were given a dichotic

listening task: through earphones they were presented with

two fugue subjects by minor Italian baroque composers,

played one into each ear simultaneously, and they were then

asked to write down the two themes on music paper which the

experimenter had provided. A numerical measure of the

degree of accuracy with which the themes were transcribed

was set up, and values of this measure were used to compute

a left-

Finally, I turn to a sociomusicological study by August

Blinddarm, who for a period of three months attended every

performance given at the Vienna State Opera and spent the

intermissions accosting people in the lobby and asking them

questions that are calculated to elicit a musical response

within a very limited range. Specifically, he asked them

the question which translates into English as ‘Excuse me,

how does the Liebestod from Tristan go?’, except that

on nights when Tristan was being performed, he was

careful to ask instead, ‘Excuse me, how does the Mad Scene

from Lucia di Lammermoor go?’. Blinddarm asked these

questions of approximately equal numbers of persons on each

floor of the Staatstoper and took care to include members of

the opera house staff as well as members of the audience.

After eliciting a response from each subject, Blinddarm

would excuse himself and, in the privacy of a cubicle in the

men’s room, would jot down the relevant characteristic of

the person and his response. The responses were of several

types. Some of the persons accosted sang the theme in

question; some hummed it; some whistled it; still others

produced from their pockets a harmonica, recorder, or other

small musical instrument and proceeded to play the theme;

one subject even played the Liebestod on his vertebrae by

striking them with a xylophone hammer, though according to

Blinddarm, his third lumbar vertebra was nearly a semitone

below the B-

Blinddarm found that the frequency of a whistling response descended steadily from the gallery to the main floor, except that its frequency was even lower in the box seat lobby than on the main floor. Humming, which was relatively infrequent among the gallery patrons, steadily increased in frequency as one moved down to lower floors, though its peak was in the box seat lobby and not on the main floor. Playing the theme on an instrument produced from the pocket showed a particularly interesting distribution, being most frequent in the gallery and decreasing as one went downwards, except that this response occurred significantly more frequently on the box seat floor than on the floors immediately above and below the box seat floor. Particularly interesting results emerged when Blinddarm formed the sums of various frequencies. The sum of the frequencies of humming and of whistling showed no significant variation from one floor to another, a result which provides striking confirmation of Blinddarm’s conjecture that humming is regarded as a socially acceptable substitute for whistling. Blinddarm’s preliminary parallel study in the Frankfurt opera house shows striking parallelism with the Vienna study: the frequencies of each response type on each floor of the Frankfurt Opera House differed only insignificantly from the frequencies on the next higher floor of the Vienna State Opera, except that the frequency with which the box seat patrons in Frankfurt pulled an instrument out of their pockets was close to zero, a fact for which Blinddarm has yet to find a satisfactory explanation.

[k] - Tell presents!

DAN JONES and the PHONETICIANS -

New album featuring: I Get a Click out of You · Cheap

Trills · Let it /b/ · Taps · and their hit single, You Drive

Me Wild with Your Bilabial Ingressive Clicks.