Hi! This is Consulting Editor David J. Peterson. You know, we have a

lot of fun here at Speculative Grammarian, but in devoting an

entire issue to the controversial yet provocative term “morphome”, we

felt it was important to include a straightforward, down-

Anyway, let’s sprinkle the biscuits and water the bulldog, shall we?

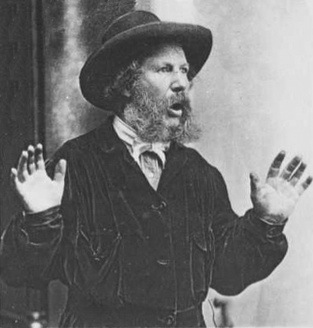

The term “morphome” was coined (or created or discovered) by linguist Mark Aronoff some time during the year 1994. Wait, that’s not right... Let’s say it was introduced by Mark Aronoff in 1994 in his book Morphology by Itself: Stems and Inflectional Classes. As a matter of fact, we have a shot of Mark that may have been taken at the precise moment that the idea of a “morphome” occurred to him:

Since that momentous occasion, practically dozens of morphologists

have been puzzling over it. Sometimes it seems like no two morphologists

define “morphome” the same way

While it would be intellectually irresponsible of SpecGram to attempt to define the term “morphome” once and for all, I can, at this point, say one thing with absolute certainty: the definition of “morphome” is not “morpheme” (and, honestly, I can’t see why anyone would suggest such a thing, as the words are spelled differently. That’s like suggesting that “defense” and “defence” mean the same thing!).

Now that that’s been settled, we can move on to what morphomes do.

Aronoff (2006) provides a corking example that helps elucidate the illusory nature of the wily morphome. I’ll do my best to replicate it here.

Say you’ve got these data...

| Present Tense | Past Tense |

| stand | stood |

| withstand | withstood |

| understand | understood |

Now, a morphemic analysis of these data would involve a lot of magic wand waving, discontinuous whatnot, or Distributive Morphological hijinks (“It’s all syntax! It’s all syntax! I’m in love with Katie Holmes!”, etc.). Aronoff dispenses with all that, and instead proposes a morphomic analysis.

First, one has to accept that the meaning of “stand” is

unrelated to either “understand” or “withstand” (i.e. there is no

standard derivational process involved here as there is with “download”

and “redownload”). If these three aren’t semantically related, then they

can’t be analyzed as “stand” plus prefix. In addition, one must accept

that this isn’t a standard morphological process

Okay! If you’re still with me so far (and I do recognize that those

thinking of the etymologies of “withstand” and “understand” may not be,

but remember the Linguist’s Motto: “Synchronic is chronic!”), then

there’s only one final step. First, the “stand/

Oh, and by that, of course, I mean the phonological “stand/

Okay, forget that example. I’ve got a great example that should make everything clear.

Okay, let’s say you have a language called...Morfomidan. Morfomidan

has seven cases (nominative, accusative, ergative, accusative 2,

subtractive, fecundive and anavocative), and probably thirty-

|

|

As you can see once you strip off the noun class circumfix2, the morphomic stem /tess/ alternates regularly with /test/ in the tetral. None of the irregular forms are related semantically, yet they all illustrate the same pattern. Thus, one might refer to /tess/ as a morphomic stem. Remember that this is an element that operates only within the morphology, and not generally in the phonology (for proof of which, note that the alternation is not present in the borrowing “stone jacket”).

Congratulations! You are now an expert on Aronoff’s morphome. You

should now be able to enjoy the rest of this special issue dedicated to

the morphome without any trouble. So, happy reading

2 All nouns in this table except for “lint” belong to the same noun class (the class 18 circumfix on “lint”, though, is, of course, irregular).